This paper was presented at the COV&R 2021. It is a reworking of chapter 10 of De overtocht: Filosofische blik op een psychose (The Crossing: Philosophical View on a Psychosis).

1. Something about Hölderlin’s Umnachtungsgedichte

Let us start with a fragment:

Die himmlischen aber,

Die immer gut sind, alles zumal,

Wie Reiche, haben diese

Tugend und Freude.

Der Mensch darf das nachahmen. Darf,

Wenn lauter Mühe das Leben,

Ein Mensch aufschauen und sagen:

So will ich auch sein? Ja,

So lange die Freundlichkeit noch am Herzen,

Die Reine, dauert, misset nicht

Unglücklich der Mensch sich mit der Gottheit.1

But the heavenly ones,

Always good, possess, even more

Than the wealthy,

Virtue and joy.

Humans may follow suit. Might,

A person, when life is

Full of trouble, look up and say:

I, too, want to be like this? Yes,

As long as friendliness and purity

dwell in our hearts, we may measure

ourselves not unfavorably.2

Are we allowed to imitate the gods? If not, why not? Does it depend on what god we want to imitate? In mimetic theory, these are core questions, theologically, anthropologically and I would add here, psychologically. They are more than touched upon in the fragment above, which is taken from Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem In lieblicher Bläue. As far as I know, René Girard never discussed this poem. In the chapter in Battling to the End entitled ‘Hölderlin’s Sorrow’ the main focus is on Der Einzige (The Only One). Before we will delve into this great mimetic question itself and start looking at the answer Hölderlin provides, I will say a few things more about this poem and its curious text history which will entail a possible explanation why this poem might have escaped Girard’s eye.

Friedrich Hölderlin created two highly different poetic oeuvres which correspond to the two halves of his life. His famous hymns and elegies, like Wie wenn am Feiertage or Heimkunft – to name a few – belong to the first halve of his life, a period we can date from the beginning of his writing up till 1802. Then there is a second oeuvre which starts in 1807, when Hölderlin is living in a tower room of a house of cabinet-maker Zimmer in Tübingen.

Hölderlin’s tower on the Neckar in Tübingen

The poems of his second oeuvre are short, simple, put in rhyme and signed by dates in the past and the future and with strange names like Scardanelli. Only in the course of the second half of the twentieth century, readers started to take these short poems serious as literary output. Yes, started I must say, and nothing more, just a beginning was made… Most literary critics still consider these poems as insignificant.3 According to biographer Rüdiger Safranski, a lot of the poems Hölderlin wrote in the second half of his live, have been lost.4 Nevertheless, one of them, Das Angenehme dieser Welt, has grown well-known, not for its literary but for its biographical value. It is worthwhile to quote this poem in full:

Das Angenehme dieser Welt hab’ ich genossen,

Die Jugendstunden sind, wie lang! wie lang! verflossen,

April und Mai und Julius sind ferne,

Ich bin nichts mehr, ich lebe nicht mehr gerne!5

World’s pleasures I enjoyed from first to last,

My youthful days, long gone! long gone! are past,

April May and July lie far away,

I’m nothing more, have no more wish to stay!

I believe every German poet lover knows this line: ‘ich lebe nicht mehr gerne.’ Hölderlin is suffering intensely.

The chapter in Girard’s Battling to the End entitled Hölderlin’s Sorrow, relates to this suffering. But what was Hölderlin suffering from? In the conventional view, Hölderlin, in the second half of his live – the years I should add here are from 1806 to 1843 – suffered from insanity. What René Girard wants to suggest in his Hölderlin chapter is that this man deemed mad had gone through something like a conversion.6 Later, in 2019, Benoît Chantre (who is also the interviewer in Battling to the End) would elaborate this in his Le clocher de Tübingen. Although I do not fully agree with Chantre and Girard, I think their ideas make sense and are worthwhile to examine. In any case, I do not believe Hölderlin was insane, psychotic or schizophrenic, in the second half of his live.7

In lieblicher Bläue can be dated at 18048, that is, right in the middle of this mysterious period between 1802 and 1806, that according to biographic conventions counts as his Umnachtungsjahre. Umnachtung is a wonderful German word pointing at becoming mad, or closer to the German original, pointing at the darkening of a mind. It is also often used for what happened to Friedrich Nietzsche in the first months of 1889, but what happened to Hölderlin is something very different from the ‘ordinary psychosis’, if I may put it like this, Nietzsche suffered.

As I said before, the poem Girard and Chantre pay most attention to in Battling to the End is Der Einzige, The Only One which is dated in 1803. Then there is another fascinating poem which I will quote in full here, which is dated in 1802 and which was published in 1805 in Wilman’s Taschenbuch, which is Hälfte des Lebens. According to Safranski, this is one of the most beautiful poems in the German language.9

Hälfte des Lebens

Mit gelben Birnen hänget

und voll mit wilden Rosen

das Land in den See,

ihr holden Schwäne,

und trunken von Küssen

tunkt ihr das Haupt

ins heilignüchterne Wasser.

Weh mir, wo nehm’ ich, wenn

es Winter ist, die Blumen, und wo

den Sonnenschein

und Schatten der Erde?

Die Mauern stehn

sprachlos und kalt, im Winde

klirren die Fahnen.

At the Middle of Life

The earth hangs down

to the lake, full of yellow

pears and wild roses.

Lovely swans, drunk with

kisses you dip your heads

into the holy, sobering waters.

But when winter comes,

where will I find

the flowers, the sunshine,

the shadows of the earth?

The walls stand

speechless and cold,

the weathervanes

rattle in the wind.10

It is a poem we may call prophetic. Apparently Hölderlin is foreseeing that the second halve of his life – and at 1806, when his production of free verse had stopped, he also happens literally to be at the middle of his life – will be one of suffering, having lost the poetic inspiration that always kept him going. In the preface to his translation in Dutch, Ad den Besten quotes this poem in full, and adds that you can sense that Hölderlin in the late poems in this period, like Der Einzige and Patmos, is losing control over language, is losing his feeling of poetic rhythm which made his poems so great. In De overtocht I write that the first time I read Hälfte des Lebens, it made me think of a psychiatric patient suffering from a severe bipolar disorder, who after a series of manic experiences would be incarcerated in a mental hospital, and would be drugged down to ‘normalcy’ for the rest of his life.

2. Girard’s discovery of Hölderlin

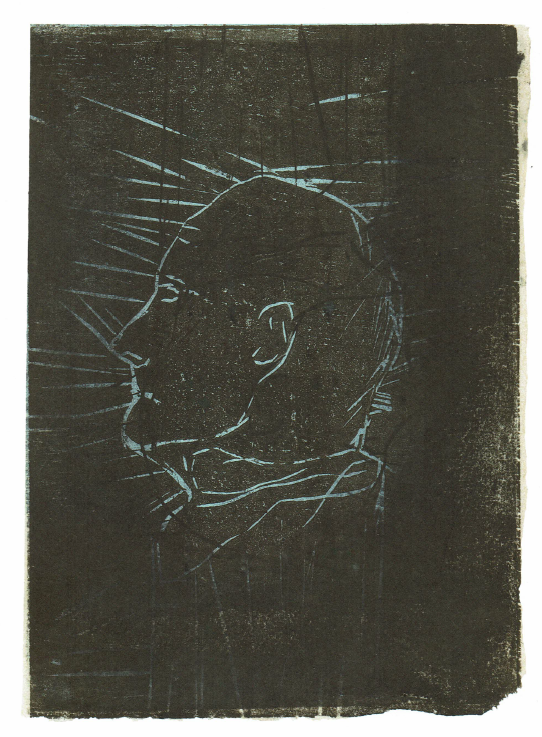

In the autumn of 2015, I visited Tübingen and the tower where Hölderlin had lived during the second halve of his live. There I bought a wonderful volume of Hölderlins Turmgedichte, with moving portraits of Hölderlin as an old man.

Portrait of the older Hölderlin

If there had been a guestbook, I certainly would have browsed it for looking whether René Girard had left an entry when he was at the same place a couple of years before. Let me quote Girard on his visit to the tower in Hölderlin’s Sorrow:

I recently visited the places where Hölderlin lived: the Stift where he met Hegel and also the tower of carpenter Zimmer. I was very moved. For me, discovering Hölderlin was a turning point. I read him during the most hyperactive period of my live I have known, at the end of the 1960s, when I alternated between elation and depression in the face of what I was trying to construct.11

In Battling to the End Hölderlin seems to appear out of nothing, and the same thing can be said about Violence and the Sacred, where Hölderlin is for the first time mentioned in Girard’s oeuvre.12 While working on a digression about thymos13(Girard translates this word as ‘soul, spirit, or anger like “the anger of Oedipus”’) and cyclothymia (we would today translate as ‘bipolar disturbance’) – all of a sudden, Friedrich Hölderlin is on stage. Girard does not shy away from entering long quotations from Hölderlin’s first draft of his novel Hyperion and one of his humble letters to Friedrich Schiller. Certainly, there is a tight knot of personal experience revolving around bipolarity, high intellectual ambitions, and questions of closeness and distance to the model (in the case of Hölderlin the most important model is, as we know, Friedrich Schiller). Neither here, nor in my book, I try to decipher this text or to untangle this knot. Because it is not my aim to draw Girard himself within psychiatric discourse. The only point I want to make is that you can still suffer from bipolar fluctuations after having gone through a conversion, as Girard himself implicitly attests.

The underlying idea Girard wants to express in this section of his Violence and the Sacred, is that the cautiousness of the chorus in Greek tragedy makes sense. There is always a looming disaster in Greek tragedy – the tragedy at hand here is Oedipus King – which is the sacrificial crisis. There is a threat of the total annihilation of the community – something we do not have to further explain for an audience familiar with the work of Girard. Just before Hölderlin arrives, Girard writes:

Some will attribute the cautiousness of the Greek chorus to a pusillanimous temperament, already at this early date imbued with bourgeois attitudes, or else to an arbitrary and merciless superego. We must be careful to note, however, that it is not the ‘sinful’ act in itself that horrifies the chorus so much as the consequences of this act, which the chorus understands only too well. The vertiginous oscillations of tragedy can shake the firmest foundations and bring the strongest houses crashing to the ground.14

And then there is Hölderlin:

Fortunately, even among modern readers there are some who do not hold tragic ‘conformism’ in scorn; certain exceptional individuals who have succeeded through genius and a good deal of pain, in arriving at a full appreciation of the tragic concept of peripeteia.

At the very portals of madness, Hölderlin paused to question Antigone and Oedipus the King. Swept by the same vertiginous movement that seized the heroes of Sophocles, he tried desperately to attain that state of moderate equilibrium celebrated by the chorus.15

How exceptional Hölderlin’s sympathy for the chorus within the area 18th and 19th century literary criticism is, I cannot say, but surely Girard is right in pointing out that Hölderlin wants to learn from the chorus’s moderation. Another way to put it, Hölderlin disidentifies from the Greek heros, or does not want to follow him in his hybris.

Doing his academic homework for Sophocles’ tragedies, Girard must have bumped on the two short pieces Hölderlin wrote surrounding his translations of Oedipus the King and Antigone in 1804.16 In the middle of his Umnachtungsjahre – writing on Hölderlin in the seventies of the 20th century, Girard still believed in the myth of Hölderlin’s madness – Hölderlin translated Oedipus the King and Antigone into German. It is in about the same time, we may surmise, when he wrote In lieblicher Bläue.

So yes, it all makes sense. Are we allowed to come near the gods? Yes, provided that we do not measure ourselves with the divinities, yes, provided that we do not fall prey to hybris. What Hölderlin is seeking after is the proper distance, or what we might call equanimity. You can get too close to the gods, entailing hybris, elation, violence… But you also can get too far away from the gods, resulting in coldness, sterility, indifference, depression. Psychiatry here is inscribed in Greek tragedy.17 In psychiatric terms, one could say Hölderlin is seeking after a medicine, a pharmakon like lithium, a ‘mood stabilizer’, a medicine that is supposed to top off the highest mountains and to plenish the deepest valleys.18 The admiration for the Greek chorus and the advice given in his poem In lieblicher Bläue are one and the same thing.

So why didn’t Girard write an article about In lieblicher Bläue? For in this poem a basic theme in mimetic theory is formulated in an almost explicit, literal way? My hypothesis is that he never wrote about this poem because he never read it. Personally, I really had a hard time at finding it in Hölderlin’s Sämtliche Gedichte published by the Deutscher Klassiker Verlag. It is neither in the chronological list, nor in the alphabetical index. I came across it because my first readings of Hölderlin’s German text was in the parallel texts of the Dutch translation by Ad den Besten, the translation I already mentioned. This is a book which aims at a larger audience. The poem may also be found in more popular German collections.

The reason it does not get a proper place in an authorized edition, is that it has never been proven that In lieblicher Bläue was actually written by Hölderlin himself. The text is quoted in the novel Phaeton (1823) by Wilhelm Waiblinger, who happens also to be Hölderlin’s first biographer. Waiblinger often visited Hölderlin in his tower, and the novel Phaeton, about a sculptor who becomes mad, is modeled on the late Hölderlin. Hölderlin often gave poems to his visitors, some of them he wrote while they were visiting him. Somehow, In lieblicher Bläue must have come in Waiblinger’s possession and in his novel he quoted it in prose. Waiblinger quoted it not in order to celebrate the swan song of an artist going mad, but as a proof of an artist already gone mad! Apparently the poem, to Waiblinger himself, was so outrageous and strange, that it could function as a proof of a delirious sculptor only able to utter gibberish.

Compilers of Hölderlin like Ad den Besten, accept In lieblicher Bläue as an authentic poem by Hölderlin. It shows a command of language and rhythm that a second-rate author like Wilhelm Waiblinger never would be able to master. Apart from accepting this poem in his compilation, den Besten also restores the prosody which has been lost. Certainly, he was not the first one to do so. Also, in Heidegger’s Erläuterungen zu Hölderlins Dichtung we find comments on fragments of this poem which are always quoted in verse.

3. Syncretism

Are we allowed to imitate the gods? Yes, we are, only if we keep at a proper distance, Hölderlin says. But who are the gods? In the poetry of Hölderlin this is a very difficult question to answer. Hölderlin’s view would make perfect sense if it would be based on an interest in the pagan gods, as we can find this for instance in Goethe or Schiller. It is Girard himself who writes time and again that the Greek gods are not imitable because they are violent gods. A truly peaceful god introduces a different economy of imitation – it is one of the main tenets of mimetic theory.

Keeping Goethe and Schiller in the back of our minds, we can say that Hölderlin differs in two respects from these looming literary figures. First, Hölderlin’s religious feelings are more serious. When undergoing his moments of inspiration, Hölderlin seriously believes he is going through something similar the Greek went through during their religious ecstasies. His own experience is telling him, the divinities of the past are within reach, they might return, they will return… The difference between Hölderlin’s poetic inspiration and the inspiration experienced by Goethe or Schiller is that there is no psychological/metaphorical intermediary. Being ‘inspired’ for Hölderlin is not ‘as if having contact with the gods’, as it was largely to Goethe and Schiller, but rather, it is the very thing itself.19 Hölderlin rates his elation as moments of being in touch with the divine itself, whereas Goethe and Schiller have a sense of going through an experience which resembles that for which our Greek ancestors invoked the name of the divinities. This is an importance difference without which the poetry of Hölderlin cannot be properly understood. It is the reason why Heidegger hardly ever inserts quotations by Goethe or Schiller in his work and focusses on poets who prove or suggest of having had experiential contact with the divine. Like, foremost, Hölderlin, but also, maybe to a lesser extent, a poet like for instance Rainer Maria Rilke.20

Then, secondly, Hölderlin tries to absorb Jesus Christ in his religious vision. In a certain sense Hölderlin is the opposite of Nietzsche who fiercely contrasts Dionysos to ‘the Crucified’. Hölderlin tries to reconciliate the two deities or thinks of the divine as something in which christian and pagan deities both have a place. When writing about this typically Hölderlinian attitude, Girard uses the word ‘syncretism’.21 Syncretism refers to the way how citizens in classical antiquity experienced the gods in another empire as transformations of their own gods. In the Hellenic world the god of the sea is called Poseidon, in the Roman empire his name Neptune. The divine world happens to be populated by similar figures in each culture, and in Hölderlin’s typical brand of syncretism Christ deserves a place, surely an important place, in the Greek pantheon of gods. When writing about wine, for instance, Hölderlin may be thinking of Dionysos, but also, at the same time of Christ. The title of one his most famous poems, Brot und Wein, a poem which is mainly about Greek deities, carries in its very title an allusion to Christianity that cannot be missed.

This syncretism in Hölderlin is present from the very start. And over the years we find Hölderlin moving more and more into the direction Christianity. This is one of the main themes in Benoît Chantre’s fascinating study Le clocher de Tübingen.22 There is, certainly, a shift in accents… The openness towards Christ is increasing while the openness towards the Greek gods is decreasing. It is a slow process that has been noticed by other Hölderlin readers as well.23 Still, it is strange to think of Hölderlin as someone undergoing a conversion to Christianity, for the simple reason – although he had broken with the type of faith present in his pietistic upbringing – he had never lost touch with Christ in the first place.

In Battling to the End, Girard is suggesting a kind of apotheosis which then must occur in the poem Der Einzige. Here, in the title of this poem, there seems to be the promise of a resolution, as if Hölderlin is finding his one true god. Whatever Hölderlin went through in his Umbachtungsjahre, he never came to a fierce opposition between the christian god and the pagan gods as we find it in Nietzsche, or in Girard himself. Hölderlin’s attitude shifted, but he never lost sight of the Greek statures in his syncretic vision. Girard also seems to realize this, when he later writes: ‘We have to be careful not to portray Hölderlin as too Christian.’24

But now we have a theoretical enigma. The more christian Hölderlin became, the less problematic would the Nachahmung of the gods turn out to be – the Girardian lens tells us. Yet, in In liebliche Bläue, this distinction between imitable and inimitable gods is not really made. One always should keep a proper distance from the divine anyway, also if we are dealing with Jesus Christ himself, is what Hölderlin seems to say. So as to the question of ‘good mimesis’, we can say that for Hölderlin distance is more important than the proper model, or the model that is beyond violence.

4. Two dimensions in good mimesis

Hölderlin’s poem In lieblicher Bläue thematizes distance as an essential aspect of good mimesis. To keep distant from the gods is a fundamental advice, and also if the divinities are becoming more christian, this distance still should be observed. A harmonious religious life for Hölderlin, is finding your gods and refrain from measuring yourself with them. We can rephrase this in mimetic terms as, becoming aware of your models while preserving the right distance. So, in good mimesis we always have two aspects. Good mimesis occurs or becomes possible when 1) there is a nonviolent model and 2) when the subject in the mimetic triangle manages to keep the model at a distance.

In Battling to the End, we can read how Girard tries to rework Hölderlin’s emphasis on distance to an exclusive relationship with Jesus Christ. Here, there is a theology behind, saying Christ is the only savior, as is also expounded in the Gospels, for instance in Acts 4:12. ‘And there is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved.’ The context Girard is thinking in is the relationship to the divine, and the position he is willing to take, might be predicated as orthodox.

Girard starts the Hölderlin chapter by saying that positive mimesis is disappearing because ‘positive models have become invisible’.25 This is a reprise of the ‘internal mediation’ described in Girard’s Mensonge. This positive mimesis is than pointed at Jesus Christ:

We […] say two things: one can enter into relations with the divine only from a distance and through a mediator: Jesus Christ. […] In order to escape negative imitation, the reciprocity that brought people closer to the sacred, we have to accept the idea that only positive imitation will place us at the correct distance from the divine.26

And:

The presence of the divine grows as the divine withdraws: it is the withdrawal that saves, not the promiscuity. Hölderlin immediately understood that divine promiscuity can be only catastrophic. God’s withdrawal is thus the passage in Jesus Christ from reciprocity to relationship, from proximity to distance.27

Girard describes the second half Hölderlin’s life as a withdrawal from the world and perceives something in his mood he calls ‘mystical quietism’.28 In my book I describe Hölderlin’s tower years as a descent. If we want to use psychopathological terminology, I simply say that Hölderlin’s case is a-typical, and that we do not have words for the descent he made. Certainly, it is neither schizophrenia nor psychosis. Benoît Chantre suggests that Hölderlin was mentally damaged because he had been mistreated during his stay in the newly opened hospital of Dokter Authenrieth in Tübingen.29 If you read about the treatment methods that became fashionable at the beginning of the 19th century in Michel Foucault’s famous Folie et déraison, this might well be the case. In the beginning of his tower years there are fits of anger, there is suffering, there is depression, but there also many fine days, when Hölderlin is playing on the harmonium in his room or going out for a walk in the beautiful surroundings in Tübingen. Traces of serenity only become visible in the later tower years. In the idea that Hölderlin withdrew right from the start into the ‘right distance’ towards the divine, I cannot believe.

Near the end of the chapter on Hölderlin, Girard keeps on putting emphasis of Christ being the unique model, whereas Hölderlin’s story is basically about distance:

“Innermost mediation” would be nothing but the imitation of Christ, which is an essential anthropological discovery. Saint Paul says, “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ.” This is the chain of positive undifferentiation, the chain of identity. Discerning the right model then becomes the crucial factor.30

And:

Benoît Chantre: Pascal had a great metaphor for expressing the leap from the order of bodies to that of charity. He talked about the distance you need to be from a painting to see it properly: neither too far nor too near. The ‘exact point which is the true place’ is nothing other than charity. Excessive empathy is mimetic, but excessive indifference just as much. Identification with the other has to be envisaged as a means of correcting our mimetic tendencies. Mimetism brings me too close to or too far from the other. Identification makes it possible to see the other from the right distance.

René Girard: But only Christ makes it possible to find that distance. This is why the path indicated in the Gospels is the only one available now that there are no longer any exempla, now that transcendence of models is no longer available to us.31

It seems to me that, at this juncture, Benoît Chantre was more receptive to what Hölderlin is really trying to say than René Girard himself.

*****

I do not believe that there are no longer any exempla. I believe there are many exempla today. They are often predicated as the ‘holy’ men or women of the modern age. I am talking about people like Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi. They may not be ‘real’ saints, in a catholic metaphysical sense (although Mother Teresa holds this status as well), but they embody something very many people admire and want to imitate. Yet also, with someone like Nelson Mandela for instance, one has to keep distance. One can get too close. There are stories of people who have been inspired by the way Mandela, after having been imprisoned for 27 years, did return to freedom as someone who was not driven by anger or resentment. As an admirer of this great man, you can apply this to your own life. Some people have been imprisoned for 27 years in a bad marriage, and they may also try to come out with a warm heart and wishing the best for their ex-spouse. Yet also, there also people who try to appropriate the glamour that inevitably surrounds human greatness. People may start to imitate Mandela’s words, his gestures, his clothes, trying to become a Mandela look-alike. In a psychosis the distance may wholly disappear, and you may find someone going to a stadium to deliver a great speech against apartheid, trying to address the audience at the moment a game of soccer is going on.

Nelson Mandela is mentioned in Joachim Duyndam’s essay ‘The Key to Freedom: The Hermeneutical Character of the Mimetic Theory.’32 I already used the word ‘inspired’ which is key to Duyndam’s considerations. This word ‘inspiration’, in the way Duyndam goes about it, will get all the ambivalences it deserves. Also criminals and dictators may inspire, so there is no reason to deny that in good mimesis the exemplum has to embody something of value. Neither is there a reason to deny that all the conflictual mimetic relationships Girard writes about exist. Yet surely inspiration can take on the shape of ‘good mimesis’:

So, the exemplary figure is not necessarily a recognized hero or saint. They can be very ordinary people from our own environment. Figures like Nelson Mandela or Mahatma Gandhi inspire millions of people, while my grandmother may only inspire me. The inspiration depends on what an exemplary figure represents or demonstrates: perseverance, courage, honesty, leniency, fidelity. I use the more general term value to indicate what the sample figure demonstrates or embodies, and what excites, appeals to, challenges, motivates – or in one word: inspires. Such inspiring values can be embodied by living exemplary figures from our own social world, but also by public figures, artists, politicians, historical figures, and also by fictional characters in films or novels.33

In good mimesis, apart from finding non-violent models, also a certain distance has to be observed. Duyndam describes this as translation, a translation from the context of the narrative of the model to the context of the narrative of the subject.

Hermeneutically speaking, the distance or gap exists in the difference between the context in which the value is represented in the story of the sample figure and the context in which I, the inspired one, live. Bridging this distance means translating the present value from one context to another; from the context recounted in the narrative of the sample figure (as well as the cultural historical context of the story itself) to the current cultural-historical context of the reader or the inspired one.34

When we strip Girard’s theological concerns from the question of good mimesis, and when we start to approach the question in a more secular and everyday way, as Duyndam does, then we can see that ‘good mimesis’ does not only consist in finding out who can function as the right model, but also on what should be the proper distance to these models. The question of good mimesis is (at least) a two-dimensional problem.

What I particularly like about Duyndam’s approach is his focus on contexts. In De overtocht I spend a lot of attention to problems of contextuality. I believe a psychosis is not a cognitive disorder, but a disorder of desire, a desire that can transfigure the context of our own world to the context of our models. Also, psychiatrists seem to catch up with this idea when they start to describe psychosis as a ‘dysregulation of contextual salience’.35 Don Quichot is a perfect example of somebody who wants to live in a context not his own, a context which, in the beginning of the 17th century, was only present in books. This allows Cervantes to play off two context zones against each other. In a psychotic appropriation you enter the context zone of your models. Regaining sanity is to leave this zone and learn to translate the exemplary stories, be they religious or not, to the context zone of your own life.

5. Walking on the water

The need for distance, the need for translating or recontextualizing the great deeds or miracles of our models is always necessary. Jesus, warding off the lustre of God, that is, warding off the attributes of kings and emperors, the crown, the scepter, cannot evade acquiring a glory by himself. The glory of the symbol and the content of the symbol are disjunct entities, that’s why the problem of good mimesis is (at least) two-dimensional. Any symbol can become glorious, also the symbol symbolizing the greatest shame. So, also here, in a paradoxical way, one again has to keep distance. There can also be blasphemy in wearing a thorny crown. One always has to keep distance, because there are no models who can guarantee distance, as Girard believes Christ does.

So, also Christ, or maybe even Christ par excellence, needs recontextualization. If some act or if some word of Jesus Christ inspires me, I have to rework the story or the words, which are two thousand years old, to my own situation, leading to new situations in which charity may take on new forms. It may be recognized as charity because it is charity, instead of a nice and recognizably biblical replay. If I am turning my other cheek in a café quarrel, everybody understands what I am doing… But I may be inspired by the same biblical words when I make a move during a management meeting. I may venture to say something which I feel I must say, although I know it will sound stupid, allowing my opponents to really hit me. No religious bells will tinkle in the background then.

As having gone through a psychosis, I am able to speak about having been too close to Christ from experience. Psychosis is lack of distance, or rather, it is absence of distance. One of the more hilarious moments in my psychosis was when I tried to walk on the water. It was in the cold winter of 1978/1979, and the canals in the place where I lived were frozen. Suddenly I had vision about cold blizzards sweeping over the lake of Galilee, freezing it instantaneously, allowing Jesus to walk on it. And so I stepped on the ice and fell through. Luckily, the canal wasn’t very deep, and I could get out by myself. I remember a few children looking at me and laughing. Instead of recontextualizing the biblical stories of stormy weather, I was trying to live in the context of the biblical story itself.

And I am not the only one who tried to walk on the water. Also, Huub Mous, a Dutch writer who has written a book about his psychosis, and more books about the difficulties of living on after psychosis, was all wet when he arrived at the hospital, because he also had tried to walk on the water on a pond in a park in Amsterdam.36 His experience with the religious was so intense and confronting that later in life he felt a need to keep out of the way of religion forever.37 In my book there are quotes from his book Jihad or verstandsverbijstering, which can be translated as Jihad or mental derangement. In this book, Mous tells the story of a family, family Verrips in the village of Weverskerk, who killed their son because they thought he was the devil. It is the latest registered case of genuine religious madness in the Netherlands, occurring as late as 1944. Christ may be without violence, but that does not mean that his glory cannot be appropriated in a very violent way. And this is more than just a psychiatric question…

My story of walking on the water is not yet finished. You do not have to be suffering from something that is named in DSM5 to try to walk on the water. In May 2017 a story circulated of Jonathan Mthethwa, a vicar in Zimbabwe, who believed he could walk on the water, stepped into a river in Africa and was eaten by crocodiles. The story proved to be spurious, but in the discussion following this fake news message, some journalists delved into history and produced a number of reports in which someone inspired by Christ, truly tried to walk on the water and finally got drowned.38

In suchlike stories, it is also clear to see what is wrong with this type of imitation. The same goes for holy men with stigmata, who are found out to have them carved into their bodies themselves. Instead of truly trying to embody the stories of the exemplary figure, people make an attempt to appropriate the magic halo of the model.

Even the perfect model cannot prevent being imitated in an improper way. You always can get too close to Christ. In Andrej Tarkovsky’s film Andrej Rubeljev there is a section named Andrej’s Passion. It starts with a solemn young man slowly walking to the top of a hill, the cross on his shoulder. The hill is in a serene, snowy landscape. We see a beautiful Russian woman weeping and falling on his feet. In the background there is ecstatic religious music. This is the way in which even the rudest peasant would like to be crucified, Tarkovsky seems to say.

Then, in a next scene, we see Andrej peeking at what’s going on in a pagan ritual at a Russian village. Naked people are running through the woods. The setting of the film is in the early 15th century in which pagan Russia still was a reality. Rubeljev is caught by surprise and the villagers ‘crucify’ him by tying him to a pole with a rope. There is no serenity here at all, and the village people abuse and mock him. A woman tries to arouse his sexual desire. The scene is reminiscent of Euripides Bacchants with a Pentheus peeking at a ritual orgy. I think Tarkovsky is posing a critical question. What is this ‘passion of Andrej Rubeljev’ all about?

Girard regularly remarks that the cross is a symbol of shame, something that tends to be wholly forgotten by modern people, be they christian or not. In Andrej Rubeljev there is a lot of beauty in the first crucifixion, yet hardly any shame. The second story is the ‘real’ one, taking part in real life. In a certain sense it is a translation from the context of the Bible to the biography of the Andrej Rubeljev, bringing the lost element of shame back into the story. On the snowhill a symbol was crucified, but at the pole in the pagan village, a real man is really suffering, for being mocked, and maybe for his struggle with his promise of celibacy.

In the mimetic triangle, the model may be without violence, but the subject may be not. Also, in the case of Jesus Christ, misappropriation is possible. There are all kinds of ways of ‘competing’ with Christ, of entering into a rivalrous relationship with Christ. This is what Girard seems to have forgotten in Battling to the End. And I use the word ‘forgotten’ deliberately, because we find one of the best descriptions of this rivalry in his first book Deceit, Desire and the Novel. I am referring to the penultimate chapter ‘The Dostoyevskian Apocalypse’ which contains a long section on Kirillov in Dostoevsky’s novel The Possessed. I will end my story with a paragraph taken from this chapter, but It is worthwhile to reread it as a whole:

Kirillov is obsessed with Christ. There is an icon in his room and in front of the icon, burning tapers. In the eyes of the lucid Verhovenski, Kirillov is ‘more of a believer than a Pope.’ Kirillov makes Christ a mediator not in the Christian, but in the Promethean, the novelistic, sense of the word. Kirillov in his pride is imitating Christ. To put an end to Christianity, a death in the image of Christ’s is necessary – but it must be a reversed image. Kirillov is imitating the redemption. Like all proud people he covets Another’s divinity and he becomes the diabolic rival of Christ. In this supreme desire the analogies between vertical and deviated transcendency are clearer than ever. The satanic side of arrogant mediation is plainly revealed.

Works cited

Chantre, Benoît (2019), Le clocher de Tübingen. Parijs: Grasset.

Elias, Michael & Lascaris, André red. (2011), Rond de crisis: Reflecties vanuit de Girard Studiekring. Almere: Parthenon.

Foucault, Michel (2013 [1961]), Geschiedenis van de waanzin. (Folie et déraison. Histoire de la folie à l’age classique.) Vertaling: C.P. Heering-Moorman. Amsterdam: Boom.

Girard, René (1986 [1961]), Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure. (Mensonge romantique et Vérité romanesque.) Translation: Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Girard, René (1977 [1972]), Violence and the Sacred. (La Violence et le Sacré.) Translation: Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Girard, René (2010 [2007]), Battling to the End: Conversations with Benoît Chantre. (Achever Clausewitz.) Vertaling: Mary Baker. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Heidegger, Martin (1963 [1951]), Erläuterungen zu Hölderlins Dichtung. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Heidegger, Martin (1984 [1942]), Hölderlins Hymne ‘Der Ister’, Gesamtausgabe Band 53. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Hertmans, Stefan (2010), Zäsur, differentie, Ursprung, ironie: Hölderlin en de goden van onze tijd. Website academia.edu.

Hölderlin, Friedrich (1988), Gedichten. Vertaling: Ad den Besten. Baarn: Uitgeverij de Prom.

Hölderlin, Friedrich (1994), Hyperion, Empedokles, Aufsätze, Übersetzungen. Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag.

Hölderlin, Friedrich (2004), ed. James Mitchel. San Francisco: Ithuriel’s Spear.

Hölderlin, Friedrich (2009), Hölderlins Turmgedichte. Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag.

Hölderlin, Friedrich (2011), In lieblicher Bläue. (In Lovely Blue.) Vertaling: Glenn Wallis. http://panathinaeos.com/2011/04/25/in-lieblicher-blaue-in-lovely-blue-a-poem-by-friedrich-holderlin/

Hölderlin, Friedrich (2019), Sämtliche Gedichte. Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag.

Kapur, Shitij (2003), ‘Psychosis as a State of Aberrant Salience: A Framework Linking Biology, Phenomenology, and Pharmacology in Schizophrenia’. American Journal of Psychiatry 160.1: 13-23.

Koning, Nico (2021), Over de waarde van woede: over opstandigheid en rechtvaardigheid. Eindhoven: Damon.

Mous, Huub & Tellegen, Egbert & Muntjewerf, Daantje (2011), Tegen de tijdgeest: terugzien op een psychose. Amsterdam: Candide.

Os, Jim van (2009), ‘A salience dysregulation syndrome’. The British Journal of Psychiatry 194: 101–103.

Sass, Louis A. (1992), Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature, and Thought. New York: BasicBooks.

Safranski, Rüdiger (2020 [2019]), Hölderlin. Biografie van een mysterieuze dichter. (Hölderlin: Komm! ins Offene, Freund!) Vertaling: W. Hansen. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

Sloterdijk, Peter (2006), Zorn und Zeit: Politisch-psychologisscher Versuch. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Vorstenbosch, Berry (2021), De overtocht: Filosofische blik op een psychose. Amsterdam, Lontano.